A Case For Venice

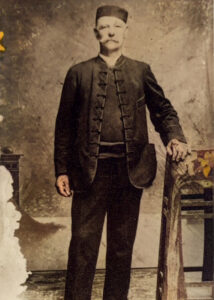

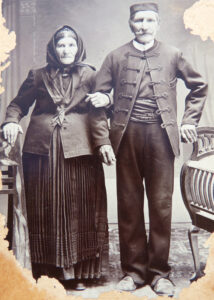

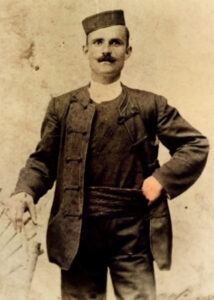

Since our pursuit for the history of the Split redcap is limited by the lack of visual and material sources predating the second half of the eighteenth century, it is fitting to turn our gaze toward the one city that bounded Istria and Dalmatia together—a shared point of influence for Pola, Split and Kotor—the storied capital of the Serenissima, Venice.

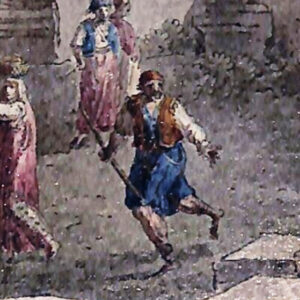

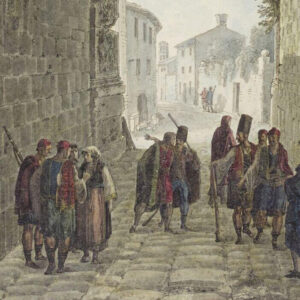

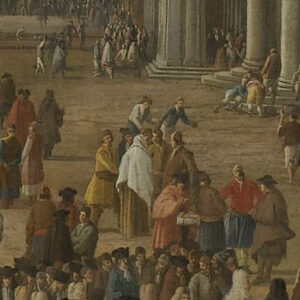

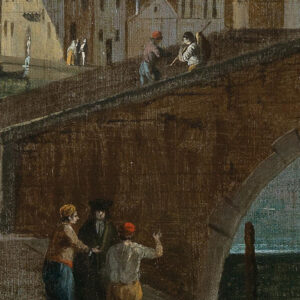

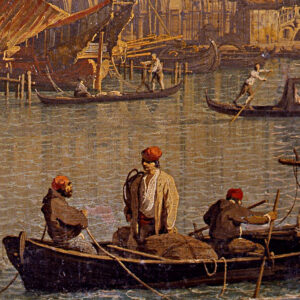

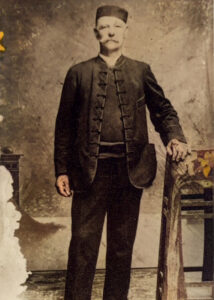

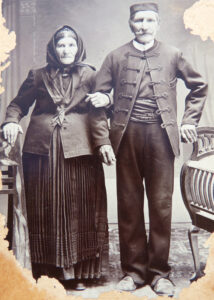

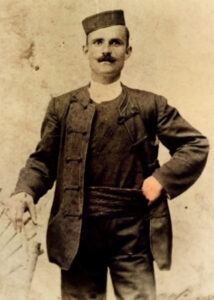

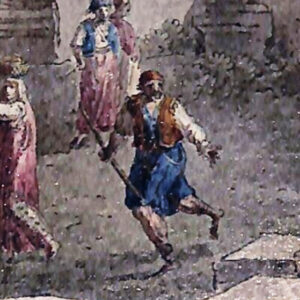

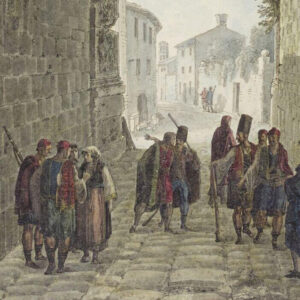

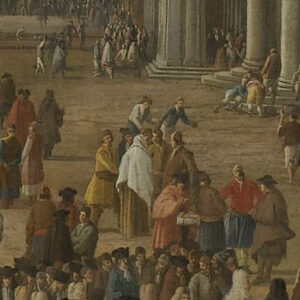

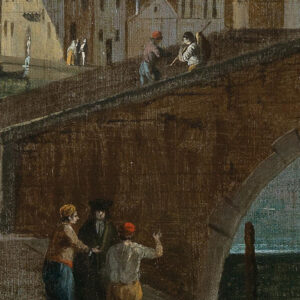

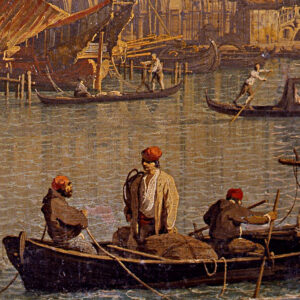

The same type of cap depicted in Cassas’s modest watercolors and engravings appears frequently in the works of the early Venetian vedutisti, particularly in the paintings and prints of Luca Carlevarijs (1663–1730), Bernardo Canal (1664–1744), and his more famous son, Giovanni Antonio Canal, known as Canaletto (1697–1768). These artists, pioneers of the Venetian veduta tradition, are renowned for their detailed portrayals of Venice’s bustling canals, harbor scenes, and civic spaces. In their numerous depictions of everyday Venetian life, gondoliers, fishermen, and laborers are often depicted with simple, functional —often red and modest in form—that closely resemble the type later seen on the eastern Adriatic coast.

These caps, consistently portrayed with a low, flat crown and snug fit, stand in marked contrast to the elaborate and decorative headwear favored by the patrician class of Venice during the same period. Their sheer number of figures wearing the cap, particularly in the time of Canaletto, suggest not only the widespread presence of this cap style among the Venetian popolani but also its probable diffusion across the Adriatic, carried by sailors, craftsmen, and traders into the urban centers of Dalmatia, including Split. The repeated appearance of these simple red caps in both Cassas’s Dalmatian scenes and Venetian vedute strongly supports the notion of a shared Adriatic material culture, shaped by centuries of political and maritime connectivity. Thus, these visual records form a crucial link in understanding how this humble yet distinctive form of headwear became integrated into the traditional attire of coastal Dalmatian townsfolk, bridging artistic representation and lived cultural practice.